ATOMOS ACQUISITION

Club Cantar partnership

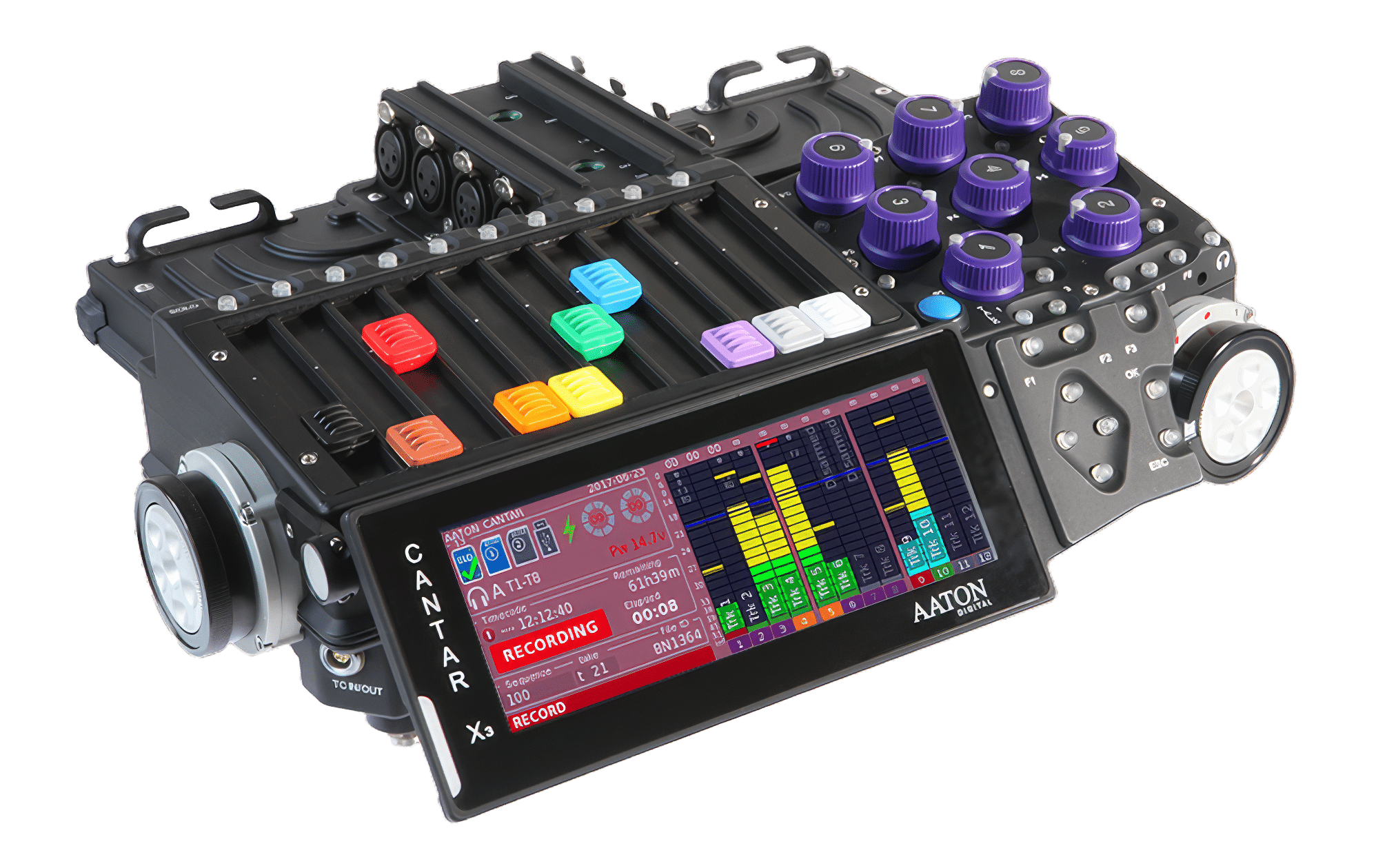

When Aaton Digital went into liquidation in 2024, Atomos stepped in to acquire the company’s assets, including the full product range, associated intellectual property, and all remaining recoverable spare parts and components.

Atomos has now announced a partnership with Club Cantar to provide ongoing repair and maintenance support for the legendary Aaton Cantar line of professional audio recorders. Supported by former Aaton engineers, Club Cantar is dedicated to keeping Cantar products alive and operational in the field.

For more information visit clubcantar.com